Narrative perspective is about who and how the story is told. In novels we can have different narrative perspectives with each a different narrator. It is important to know who is talking, because it says something about the reliability of the narrator.

We often tend to trust the narrator. For an omniscient narrator we normally can. However, especially with the first- and second-person narrator, we should be aware that the narrator has a narrow view on a situation, is biased because he or she has limiting characteristics, or simply is mad. Always be on your guard, as the author at times tries to trick the reader by a deceptive narrator.

First person

When a story is written from the first-person point of view, the narrator is a character in the story who tells the story using the pronoun I. He or she has a limited point of view and will give the reader incomplete or even incorrect information. You can have a first person central or a first person secondary.

First person central. The main character makes his own ideas, thoughts and excuses. Probably more popular in novels of growing-up than in any other sub-genre.

“I want my readers to participate in the scene I am about to replay; I want them to examine its every detail and see for themselves how careful, how chaste, the whole whine-sweet event is viewed with what my lawyer has called, in a private talk we have had, “impartial sympathy.” So let us get started. I have a difficult job before me.”

Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

First person secondary. The character is standing next to the hero and recounts their story. The narrator has their own ideas and opinions and you might wonder if they give an accurate, truthful account of the main character.

“When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever; I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart. Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction – Gatsby who represented everything for which I have an unaffected scorn.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Second person

With second-person point of view, the narrator uses the pronoun you to address the reader directly. This form is very rare.

“You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this that this time of the morning. But here you are, and you cannot say that the terrain is entirely unfamiliar, although the details are fuzzy.”

Jay McInerney, Bright Lights, Big City.

Third person

With third-person point of view, the narrator is an outsider to the story who reports the event of the story to the reader. The narrator refers to the characters either by name or by the pronouns he and she.

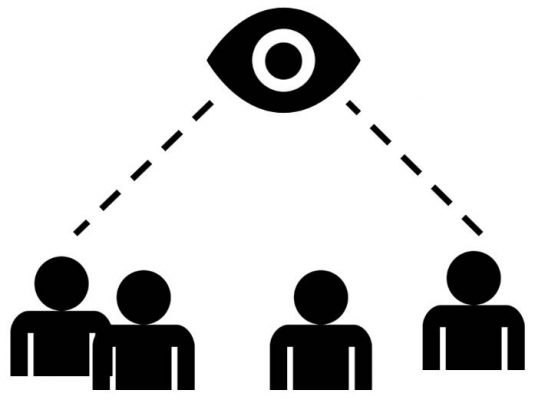

Third person omniscient (sometimes listed as simply “omniscient”). This is the “godlike” perspective on a story. and was especially used in the nineteenth century. This narrator can be everywhere in his creation at once, so he always knows what everyone is thinking and doing. An omniscient narrator cannot often foresee the future, but is completely aware of what is happening at the moment. “I” can be used, but that usage would be subject to the omniscient narrator, like a diary entry.

“For the next eight or ten months, Oliver was the victim of a systematic course of treachery and deception – he was brought up by hand. The hungry and destitute situation of the infant orphan was duly reported by the workhouse authorities to the parish authorities. The parish authorities inquired with dignity of the workhouse authorities, whether there was no female the domiciled in ‘the house’ who was in a situation to impart to Oliver Twist the consolation and nourishment of which he stood in need.”

Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist

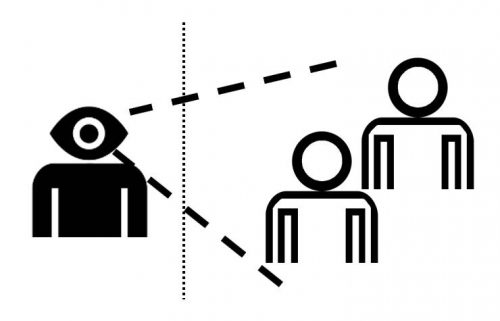

Third person limited. Like the omniscient narrator, the narrator is an outsider to the action, usually unidentified as anything other than a voice. This one, however, only identifies with one character, going where she goes and seeing what she sees, as well as recording her thoughts. It provides a fairly one-sided view of action, although this is not the impediment it might seem.

“And Farouk wondered why Martha had chosen a story so sad, why she had made their daughter cry, and he realized that every other passenger had fallen silent and they were all looking at his wife, and the only light there in the hold was from the slit along the jamb of the hatch above them and from the torches of phones, but he could see that some of the women and the girls had tears in their eyes, and some of the men had thoughtful expressions, and some looked angry […]”

Donal Ryan, From a Low and Quiet Sea

Third person objective. The narrator sees everything from the outside. Thereby only offering only external hints at the characters’ interior lives. It is as if the narrator is an invisible guest, recording everything he sees or hears.

“The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the felt pads and the beer glass on the table and looked at the man and the girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun and the country was brown and dry.

‘They look like white elephants,’ she said.

‘I’ve never seen one,’ the man drank his beer.”Ernest Hemingway, “Hills Like White Elephants”

Implied author

We speak in novels of the implied author, the voice that tells the story, because is not the actual author who is telling us the story. Everything in a novel is artificial, including the narrative voice. When you read Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens, he might have put down the words on paper, he is not the narrative voice. Therefore the opinions expressed by the narrative voice are not automatically the opinion of the author.

Free indirect Style

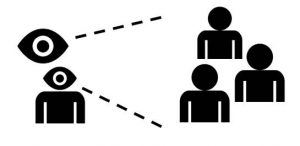

With free indirect style the implied author and a character mingle when telling the story. With free indirect style we get the overal information from the implied author, but also the narrow views and opinions from the character.

With free indirect style the implied author and a character mingle when telling the story. With free indirect style we get the overal information from the implied author, but also the narrow views and opinions from the character.

“He looked at his wife. Yes, she was tiresomely unhappy again, almost sick. What the hell should she say?”

from James Wood, How Fiction Works

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Be the first to comment